Weaver’s daughter Sophia has Rett syndrome, a neurological disorder that impairs brain development

Internet trolls have used photos of Sophia to advocate for abortion

CNN —

Natalie Weaver knows there aren’t many little girls like her daughter Sophia.

The nine-year-old has been through enough surgeries to last several lifetimes. Though she can’t talk, she uses her eyes and makes little sounds to communicate with her family. Weaver says that although her conditions sometimes cause her pain, Sophia is a happy, strong little girl.

And yet, every day people tell Weaver that Sophia should die. Or, even worse, that she should never have been born.

Sophia was born with facial deformities and deformities to her hands and feet. When she was one, she was diagnosed with Rett syndrome, a neurological disorder that impairs brain development, permanently robbing young children of language and motor functions. As a result, Sophia depends on her family for 24/7 care.

“She’s had 22 surgeries,” Weaver told CNN. “She has a feeding tube. A colostomy bag. She has seizures and choking spells because of both the deformities and the Rett syndrome.”

Weaver, a health care activist, calls her daughter amazing. But to some cruel, faceless voices on the internet, Sophia is an easy target for abuse.

One particularly cruel tweet led Weaver on a months-long struggle to do what she’s always done, what any mother would be moved to do: Protect her daughter.

Weaver, of Cornelius, North Carolina, is no stranger to internet trolls. Two years ago, a proposed policy change regarding Medicaid in her home state prompted her to be more outspoken about her daughter’s condition.

The horrifying messages started rolling in.

“People, they seek you out and want to hurt you,” says Weaver, who also has two younger children. “There are people who go out of their way to make sure you see their cruelty. I get people telling me to kill my child, to put her out of her misery.”

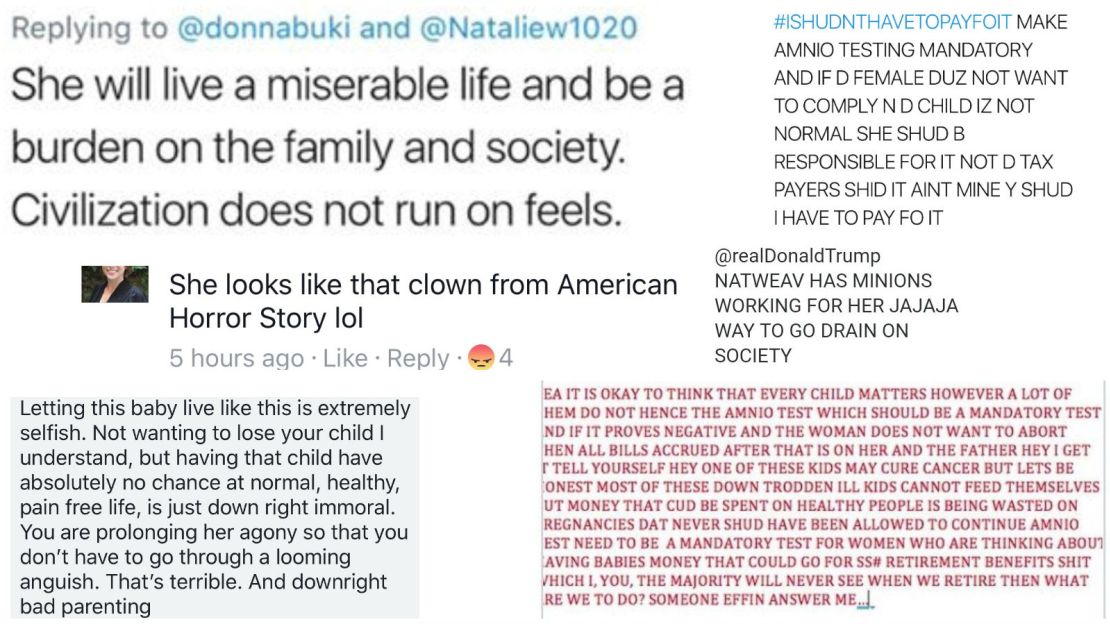

In November, Weaver received a particularly vile tweet: A photo of her daughter, along with a paragraph advocating for coerced abortion and practices tantamount to eugenics.

“Yea it is okay to think that every thing matters however a lot of them do not hence the amnio test,” read a message attached to the tweet. (The “amnio test” refers to amniotic testing, which can sometimes alert expectant parents to abnormalities in a developing fetus.)

The post went on to suggest that parents who do not choose to abort a fetus found with abnormalities should pay for “all bills accrued after that.”

The person who made the hurtful post wanted Weaver to see it: They tagged her Twittter handle and sent her a direct message.

Weaver reported the tweet and asked her followers to report the post.

“I blocked it. I just hoped it was gone,” she said. “But it was never removed. The account remained.”

Some of Weaver’s supporters told her they reported the tweet, then received messages from Twitter saying the tweet was found to be “in violation of Twitter rules.” But Weaver says Twitter sent her a message saying the post did not violate their policies.

Then, in January, people started alerting her to the fact the tweet was still up – and the troll was still active.

“[The troll] was mentioning my name and reaching out to my followers on Twitter,” she says. The post, and her responses to it, netted more horrible messages.

“She will live a miserable life and be a burden on the family and society. Civilization does not run on feels,” one tweet read.

“#ISHUDNTHAVETOPAYFOIT” read another.

Once the incident became public, people began to use it in a debate about abortion rights.

Despite the onslaught, the original tweet mattered most to Weaver because it used Sophia’s picture.

She asked people to report the tweet again and estimates that thousands did so. She also told her story to a local news station, hoping to put pressure on Twitter to take the post down.

After about a week and a half of nonstop coverage in January of this year, Weaver says she got another message from Twitter.

“[They said] they made a mistake. Twitter had it in their policy to protect people with disabilities against hate.” However, Weaver says they told her their reporting tool didn’t have enough space to include the disability category as a reason for reviewing a tweet.

Weaver was satisfied that Twitter removed the offensive post. But she also wants Twitter to change the way they review such content.

“Twitter needs to add people with disabilities as a category in their violation reporting,” Weaver says. “Otherwise people don’t know the appropriate category to select for hate towards people with disabilities.”

A Twitter spokesperson referred CNN to the platform’s “hateful conduct policy,” which says, “You may not promote violence against or directly attack or threaten other people on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or disease.”

“All of these considerations are taken into account when reviewing reported violations of the Twitter Rules,” the spokesperson told CNN.

The company’s hateful conduct policy also outlines how possible offenses are identified and how punishments are enforced. The policy states that Twitter takes into account the context of a tweet as well as the history of an account.

It also says that mass reporting doesn’t speed the removal process. “The number of reports we receive does not impact whether or not something will be removed,” it reads.

Weaver notes that Twitter isn’t the only place people sling their hurtful words. She gets a lot of hate on Facebook too. But Facebook’s reporting feature already has a category specifically for attacks against “people with disability or disease.”

Weaver is a founder of Advocates for Medically Fragile Kids, an organization that strives to preserve the rights of children like Sophia. She is also on the founder’s council for the United States of Care, a non-profit that fights for accessible, affordable solutions for health care.

In her public appearances, Weaver tries to clear people’s misconceptions about Medicaid and educate them about its importance to people with disabilities and preexisting conditions.

What’s driving her is simple.

“Without health care, my daughter would die,” she says.

As any person with a public mission knows, trolling comes with the territory. But Weaver has noticed the attacks on her daughter have become more political as health care continues to be a big national conversation.

“Someone will say [Sophia’s] undeserving of health care and is a drain on society and she should die,” she says. “People are so much more bold now to attack people with disabilities.”

There is one fundamental truth that Weaver says people don’t get – or simply refuse to admit. Sophia is a person like any other person. A daughter like any other daughter. And she is loved as one.

“I think many times, people don’t even view Sophia is a person,” Weaver says. “I know it happens with other people with disabilities. And people view her as a disability, but I just want them to look at her as my child.”

Weaver readily confirms that life with a child with profound disabilities can be difficult and painful and emotional. But to her, that’s not the most important part of Sophia’s story.

“We have to deal with so many challenges, but because of her my life is better,” Weaver says. “I know what true happiness is.”