Born in Rosario, Messi only spent a short part of his childhood in the city. But even that, the Argentine superstar left behind sweet memories with his friends, neighbors and relatives.

Located south of Rosario, the General Las Heras neighborhood, where Messi was born more than 30 years ago, is a quintessentially Argentine community. Passionate and deeply divided over the game of football, the road that runs through the neighborhood is steeped in intense love and fierce rivalry.

It is a “battle” between the hinchas (fans) of Newell’s Old Boys and Rosario Central. The battle is not just on the pitch. It is not in the stands. It is a daily battle. It reaches every corner of the neighborhood, as well as the entire city of 1.2 million built along the Parana River and three hundred kilometers north of Buenos Aires.

The Parana River is not as deep as the hatred between the fans of the two clubs representing the city. On the facades, sidewalks, electric poles, on every street corner, no identity of Rosario escapes this fierce duality. Red and black symbolize Newell’s Old Boys. Blue and yellow represent Rosario Central.

People from both sides – not just fans of the two clubs – mark their territory with graffiti in the colours of their respective teams. In Messi’s neighbourhood, the green and yellow colours dominate the urban landscape. This means that Canalla fans are overwhelmingly in number. That doesn’t stop Messi’s family from cheering for La Lepra.

However, few people expected that Messi’s father, Jorge, was not as crazy about football as his neighbors. The love of football of his three sons, especially Lionel Messi, was passed down from his mother’s family, the Biancucchi family of his grandmother Celia. Like Lionel, Emanuel and Maximiliano, his cousins also pursued a career in football. The first played for Munich 1860 and Girona. While the second wandered between Paraguay and Brazil.

For Leo Messi, the first turning point that led him to the round ball was at his grandmother’s house in 1992, a lucky year for Newell’s, when Marcelo Bielsa led the team to the Copa Libertadores final and won the Argentine National Championship. “I first touched a ball when I was 5 years old,” Lionel Messi confided in his memory to La Nacion in 2010. “My father told me that that day at my grandmother’s house, my cousins called me to play for two teams. I didn’t dare to play, but when I touched the ball for the first time in my life, everyone was amazed.”

It was not just his grandmother’s house that started it all, but it was her who first sparked Messi’s football career. Celia took him to meet his older brothers Matias and Rodrigo, who were also big names in the city and were playing for the local youth team Grandoli.

This story has become an anecdote: One day, when the team was short of players, Mrs. Celia suggested to the coach that her grandson, Leo, was a very good soccer player. After just a few dribbles, the boy attracted the attention of everyone on the field. Later, every time Leo Messi scored a goal, he would point his hands to the sky to celebrate. This action was to dedicate the goal as well as to remember his grandmother, who passed away in 1998.

Diego Vallejos, a childhood friend of Messi, said: “His grandmother was everything to him. One day, when we never dared to cross the intersection, Leo asked me to go with him to the cemetery where his grandmother was buried, a few kilometers from the neighborhood. We got on a bus, but it stopped quite far from our destination. So we walked: throwing stones at each other, kicking the butter pipes, ringing other people’s doorbells and running away… Leo walked and remembered the vague path to the cemetery. Then we got lost.”

As night fell in Rosario, the children’s parents on the other side of town began to worry. “We spent the whole evening trying to find our way home,” continued Diego, whose sister is married to Messi’s brother Matias. “We had so much fun making shoes out of scrap metal from cans and walking like robots. When we got home, we even found a fan that was still working. That’s one of my best memories. And I think Leo’s too.”

Like many children, Leo would play football in front of the family home in the General Las Heras subdivision – a two-story concrete building that still stands today – or on a vacant military-owned plot at the end of Estado de Israel. “In inter-neighborhood games, Leo would dribble past one big boy after another, get beaten, fall down, cry… but get up immediately and continue playing football,” said Messi’s uncle, Claudio Biancuchi.

“When it rained and the drains were clogged, we said we were playing water polo,” Diego Vallejos said, laughing. “He was the first to score six goals. But Matias said the games ruined Messi’s childhood. Because Leo didn’t like to lose, and even though he was the youngest, he was very nervous. So we had to play until he won.”

Leo Messi is extremely allergic to failure. That is acknowledged by those around him. “He was a bad player. When he lost, he would cry,” Jorge Messi said of his son in an interview broadcast in Argentina, at the time Messi was just emerging at Barcelona. “When he played football with his brothers, if he lost, he would cry. And the same with the cards: if he lost, he threw them away and the game was over.” Duegi Vallejo commented: “I am sure that it is this nature that pushes him to break one record after another.”

At school, Lionel Messi was much quieter. Like the superheroes in comics, he was the type of person who did not fit in because he could not use his superpowers. Despite being short and light, Messi often sat at the back of the class, his hands never leaving his desk. His classmates called Leo “Piqui”, because of his small face and body. And Piqui hated to say it. Cintia Arellano, Messi’s best friend, almost always had to be by his side to act as “transaction agent”, especially when the Argentine football genius was questioned by the teacher.

But when the bell rang for the break, this little boy, no bigger than a fist, transformed. His chronic shyness disappeared. On the field, Messi always liked to control the ball and everything. That’s why he was always chosen as captain.

“On the field, he was a leader,” recalls Diana Ferretto, a teacher at Rosario School No. 66. “The other kids always wanted him on their team because they knew that with his little feet and his incredible dribbling ability, he would win every game. He was the little prince, and his peers admired him because he had a special power with the ball.”

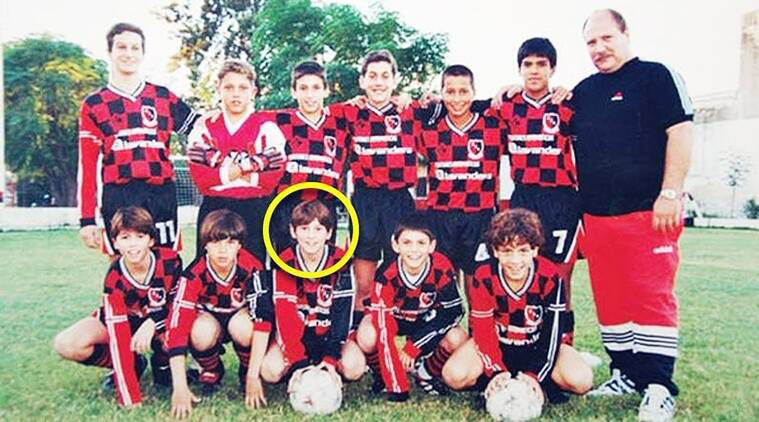

Lionel Messi left Grandoli to join the youth team of Newell’s Old Boys when he was six and a half. He and his first coach, Carlos Marconi, had a deal: Every time he scored, he would give him an alfajor (chocolate biscuits, jam and milk). If he scored with his head, the prize was doubled. “Sometimes he would dribble past the goalkeeper, then flick the ball and score with his head,” Marconi revealed to Anfibia magazine.

One day, Leo scored six goals and decided to share the reward with his teammates. Noticing that his prodigy had given away all his cookies (a team of seven), Marconi burst into tears. At Newell’s, Messi was matched by talents of his own. “La Maquinita del 87” (The Little Destroyer of ’87) crushed all opponents. Diego Rovira, the number 9 of this invincible team, recalled: “We won by such a large margin that I don’t remember the result. I just stood right in front of the goal and waited for Leo to pass the ball. I scored a series of goals like that.”

“We were in a tournament where the winner got a bicycle,” Agustin Ruani, another of Messi’s teammates, recalls one of his most illustrious memories. “For us it was a great reward, but we had to start the game without Leo. He was locked in the bathroom at home for breaking a tile and only emerged after half-time of the final, when we were 2-0 down. The game ended 3-2 and he was the one to thank.”

Alejandra Geuna, Agustin’s mother, emotionally recalled Leo’s noble attitude towards her son: “The team went to play a tournament in Peru. Agustin couldn’t go but Leo, when he returned, gave him the captain’s armband. You see? He was only 10 years old at the time.”

When not playing on the pitch, Maquinita challenges each other in the virtual world . “We spend the afternoon playing Nintendo at my house,” says Diego Rovira. “My father is a doctor. He often goes to conferences in Europe and comes back with gifts, including club jerseys. When we play together, we take turns wearing the jerseys, but Messi always chooses the Barca jersey, half blue, half red, with Rivaldo’s name on it. Because I’m two heads taller than him, the shirt is too big. He wants to keep it.” “With us, he’s not shy,” adds Agustin Ruani. “He looks at you with a mischievous smile, throws the ball at you and runs away.”

Nothing seemed to stop Messi, even when his “growth hormone deficiency” was discovered at the age of nine, when he was only 1m27 tall. “He always walked around with a little red bag, with a syringe and a dose of hormones in it,” Diego Rovira recalls. “When he was 11 or 12, he would sneak off to a place to inject himself.”

“He will be taller than Maradona,” promised Diego Schwarzstein, the endocrinologist who diagnosed the condition, which affects one in twenty thousand children. But the treatment is expensive and Jorge Messi, a workshop manager at the Acindar metallurgical company, can no longer afford it. Neither Newell’s nor River Plate want to shoulder the cost. Messi has a trial at Barca.

It was time to say goodbye. “Just before he left for Spain, we had a little party in the street in his honor, with sweets, cookies and soft drinks, like a birthday party,” said Diego Vallejos, who attended Messi’s wedding in the Rosario church.

“We see each other every time he comes back. He hasn’t changed much, he still acts like a normal person. He still comes to see us despite the difference in fame and money. We are like brothers. When we meet again, everything is like yesterday,” Agustin Ruani happily said.

Residents of the General Las Heras neighborhood say that once or twice a year, a black four-seater car drives down Estado de Israel Street before stopping briefly in front of house number 525, then continuing on. For them, there is no doubt: The person in the car is the owner of 7 Golden Balls.