A mother’s instinct means everything, and for Amanda Locke, it changed her daughter’s life.

When her little girl Imogen was born, Amanda knew something wasn’t right.

Imogen was delivered with an egg-shaped head. Amanda’s doctors said that this wasn’t anything to be alarmed about and that it should rectify itself soon enough.

But despite reassurances by medical staff, Amanda, who lives in Queensland, Australia, knew there was something seriously wrong with the shape of her daughter’s skull.

“She was a C-section baby, there was no way her head should have been the place it should have,” she recalled.

Amanda said that her little girl’s head was so deformed, it was the shape of a football.

“Her head was shaped like a football. You could see and feel the ridge,” she said.

“It was obvious that something wasn’t right and if that was going to self-correct itself in six weeks, then I was also going to win lotto. There was just no chance,” she explained.

While her last pregnancy scan showed that Imogen’s ear-to-ear measurements over the face were small, no alarms were raised over her child’s health.

Amanda, like any mother, began raising questions – Is there something wrong? How do we fix it? What can we do?

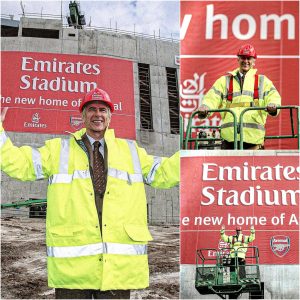

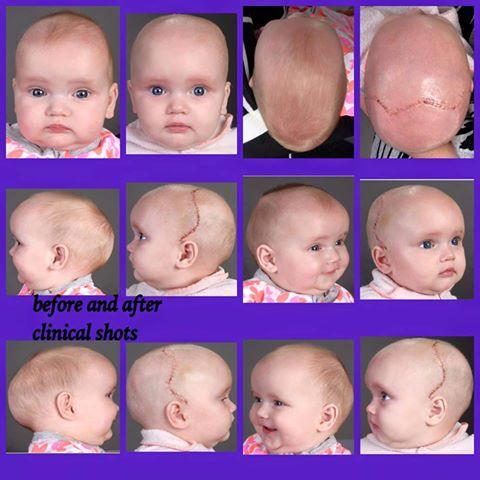

Imogen’s head at 14 weeks.

For Amanda and her family, seeing the doctor was a tough task. She lives in central Queensland, her obstetrician and closest hospital is an hour and a half away, and the regional hospital, Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital, is all the way in Brisbane. So it’s fair to say her resources were limited.

Amanda raised the issue with her local GP, but he hadn’t had much experience of the condition and was baffled.

So with no other option presenting itself, she was forced to do what a parent shouldn’t have to – self-diagnose her own baby girl.

She researched and researched and finally came across a condition to which all the symptoms matched that of her newborn daughter – sagittal craniosynostosis.

“The Google images frightened the life out of me,” Amanda said.

Imogen’s skull was fused prematurely which meant her head would be forced to grow long and narrow, not wide. As a result, the brain’s growth is restricted and often creates an abnormal head shape. The condition occurs in one out of every 2000 live births.

Amanda was referred to a paediatrician so they drove three hours for an appointment where Imogen had a CT scan. After the scan, her paediatrician confirmed the diagnosis.

The only treatment for her little girl was to undergo major surgery. This entailed removing her scalp, cutting the skull away, removing and remodelling her forehead and her occipital bone (rear of her head) – all at five months old.

“We were sent to Townsville, chose to travel to Brisbane and also consulted via Skype with the LCCH neurosurgeon to amass as much information and opinions as possible. We were way out of our depth,” said Amanda.

It was through further research on the internet that she came across a Facebook support group for mums with cranio-affected children.

Amanda had an influx of parents suggesting to get in touch with a unit in Adelaide dedicated to treating facial deformities. This is when she came across a man named Professor David David who founded the Australian Craniofacial Unit (ACFU) in Adelaide.

The ACFU is the only one of its kind in the country, and there is just one other in the world – Texas. When he founded it in 1975, Professor David recognised the need for specifically trained multidisciplinary treatment for people who are born with deformities such as little Imogen, and also victims of facial injuries.

After Amanda contacted him via email, he called her that afternoon and little Imogen was booked in for surgery the next week.

The ACFU is a multi-disciplinary unit, as it looks after the skull and therefore every body part linked to it. Prior to the op, the family saw an ear, nose and throat surgeon, training doctors, a neurosurgeon, and an eye doctor – all ensuring Imogen had the greatest care available.

It was quite an intense surgery for anyone to go through, especially a little bub.

“Her eyes swelled shut, she couldn’t see for a few days. It was difficult to pick her up because her head hurt. They cut away a part of her skull and it grew in 12 weeks. You could literally feel the brain under the skin. That was the scariest part.”

It’s now been 12 months since the surgery and little Immy, now 16-months-old, is doing remarkably well. The family will be going back every year for check-ups until Imogen‘s 16 or 17, but Amanda is incredibly proud of how well her daughter is doing.

Immy’s scar (from ear to ear in a zig-zag line) is barely visible beneath her beautiful blonde locks, and Amanda describes her as a bubbly, happy child.

“She’s brilliant. We call her Dora because she just explores every day. She’s a typical, normal little girl. Her head’s perfect. Everything is as expected,” Amanda says.

Words: Jacqui King