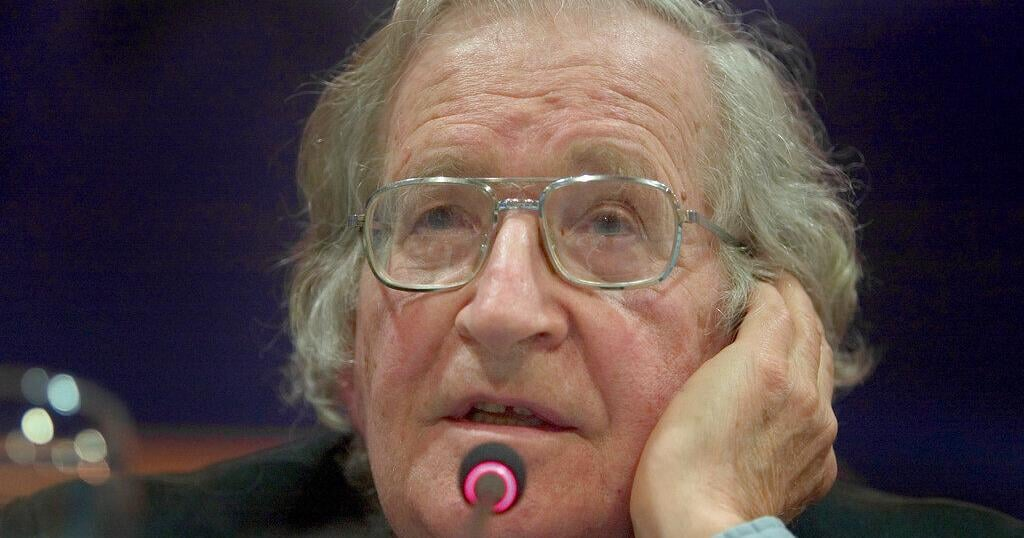

Noam Chomsky turned 96 last week. That’s a venerable age for the man who was aptly described in a New York Times book review published four decades ago as “arguably the most important intellectual alive today.”

He was 50 then. Remarkably, as the decades passed, Chomsky maintained his status, not just as our most widely known public intellectual of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, but as a courageous commentator on the issues that so much of our media — and so many of our political leaders — tend to neglect. Indeed, when Chomsky entered his ninth decade, the German international broadcasting service Deutsche Welle aptly observed that he was “arguably the foremost political dissident of the last half a century.”

That article was titled: “Dissident Intellectual Noam Chomsky at 90.”

Chomsky has faced health challenges that have slowed him down a bit in recent years. Yet his long history of public engagement continues to remind us that intellect and dissent go together, and that the vital challenge of our times is to maintain “an independent mind.” That’s not easy in an age of manufactured consent, but it remains possible to make a mark, as Chomsky has illustrated by challenging the lies of our times.

Chomsky and I have known one another for decades. On our last long visit, which took place several years ago, he was as gracious, witty and blunt as ever. He pulled no punches, decrying the flaws of capitalism and politics, sparing few politicians and no parties.

The academic and activist, whose outspoken opposition to American imperialism earned him a place on former President Richard Nixon’s “enemies list,” answered a question several years ago, (from Amy Goodman of “Democracy Now!”) about the approach of the Republican Party of Donald Trump to climate change: “Has there ever been an organization in human history that is dedicated, with such commitment, to the destruction of organized human life on Earth?” His answer: “Not that I’m aware of.”

Much has been said about Chomsky’s contributions to our intellectual and political life. I’ll offer just a few more words to the discussion of his great contribution to our discourse in the form of a snippet from an extended conservation we had several years ago about the challenges facing independent thinkers in perilous times.

Chomsky recalled a preface that George Orwell wrote for “Animal Farm,” which was not included in the original editions of the book.

“It was discovered about 30 years later in his unpublished papers. Today, if you get a new edition of ‘Animal Farm,’ you might find it there,” he recalled. “The introduction is kind of interesting — he basically says what you all know: that the book is a critical, satiric analysis of the totalitarian enemy.

“But then he addresses himself to the people of free England; he says: You shouldn’t feel too self-righteous. He said in England, a free country, I’m virtually quoting: Unpopular ideas can be suppressed without the use of force. And he goes on to give some examples, and, really, just a couple of common-sense explanations, which are to the point. One reason, he says, is the press is owned by wealthy men who have every reason not to want certain ideas to be expressed. And the other, he says, essentially, is: It’s a ‘good’ education.”

Chomsky explained: “If you have a ‘good’ education, you’ve gone to the best schools, you have internalized the understanding that there’s certain things it just wouldn’t do to say — and I think we can add to that, it wouldn’t do to think. And that’s a powerful mechanism. So, there are things you just don’t think, and you don’t say. That’s the result of effective ‘education,’ effective indoctrination.

“If people — many people — don’t succumb to it, what happens to them? Well, I’ll tell you a story: I was in Sweden a couple years ago, and I noticed that taxi drivers were being very friendly, much more than I expected. And, finally, I asked one of them, ‘Why’s everyone being so nice?’ He pulled out a T-shirt he said every taxi driver has, and the T-shirt had a picture of me and a quote in Swedish of something I’d said once when I was asked, ‘What happens to people of independent mind?’ And I said, ‘They become taxi drivers.’”

Or Noam Chomsky.

John Nichols is associate editor of The Capital Times. [email protected] and @NicholsUprising.

Share your opinion on this topic by sending a letter to the editor to [email protected]. Include your full name, hometown and phone number. Your name and town will be published. The phone number is for verification purposes only. Please keep your letter to 250 words or less.