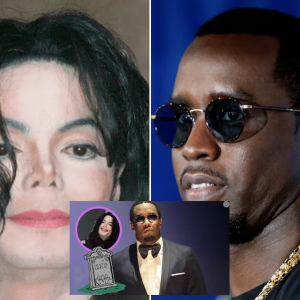

Photo: Erana Pound @thecultureofgrace & @rachelmaianz

Rachel Māia lets the water lap gently over the toes on her left foot for the last time.

It’s mid-February and the 35-year-old and some close friends are at Titahi Bay beach, with its multi-coloured boathouses framing the shore, waiting for dawn. As the sun breaches the horizon Māia swings Taonga pūoro – its note hangs in the air, mingling with the noise of waves splashing onto the sand.

The impromptu early morning gathering is Māia’s way of saying goodbye to the “hurt, pain, suffering and hate” she has tolerated since the accident 20 years ago.

Three hours later she sits on a hospital bed, playing games with her cousin to keep her mind occupied. It’s not long now.

A nurse visits and attaches a bright pink sticker to her wrist band. It reads “return body parts”. Māia recoils. In 15 minutes her left leg will be amputated below the knee, and the reality is hitting.

Māia has chosen this but that doesn’t mean this moment is easy. She tries to find some inner peace before going under the knife. She replays the “beautiful, spiritual” moment at Titahi Bay in her head over and over as the doctors prepare her for surgery.

Māia is a vivacious, driven athlete – a champion rock climber. Sport has long been important to her. As a teenager she enjoyed and found solace in exercise, and it grew to become part of her identity. Scaling great heights, over rocks and walls particularly gripped her.

But at 16, while on a school climbing trip in the South Island, everything changed when she fell. She did everything right – she had a spotter, she took a controlled fall – but she landed awkwardly on a crash pad that had not been repaired correctly.

Her right ankle suffered a minor break. Her left was wrecked – the cartilage sheared off and the bones shattered.

Multiple surgeries ensued, including one in which bone from her hip was removed then affixed to her ankle, internal screws were inserted to keep it secure.

A long, arduous process of recovery and rehabilitation followed. Māia had gone from a keen rock climber to a wheelchair user and she struggled not only physically but psychologically.

She struggled with self-esteem at high school, where she was called a “cripple”. In adulthood she was called an “invalid”; labels spoken both in careless jest, and in deliberate spite for the next 18 years.

“You can find yourself being given labels you didn’t choose for yourself. [But] there became a defining point; I get to choose the life I have and the attitude I have to it. I had to decide what I believed about myself.”

In the two decades since her accident, Māia has undergone nine surgeries on her ankle, including numerous debridement operations to remove bits of bone and cartilage growing in the wrong place. Mobility has come and gone but ultimately the treatment didn’t allow her to live without pain or with full autonomy.

Five years ago Māia was one of the first New Zealanders to undergo an experimental treatment that involved having a traction frame mounted on the outside of her leg, bolted through her flesh and bone. For four months she had to “tinker” with the frame, adjusting screws and bolts with a set of spanners. This was to stretch her ankle out and encourage cartilage to grow. She looked like a transformer, according to her children, who are 8, 11 and 13 – the eldest has “magical superpowers” – autism and an intellectual disability.

The experimental treatment doesn’t have a high success rate in New Zealand, but Māia was determined to try it – for herself, and her children. The operation was a partial success and she was able to start walking very short distances with one crutch. She also relied heavily on an i-walk – an artificial leg-type device that allowed to her manage basic activities like housework or making her children breakfast.

“I said to [my son], ‘Do you remember when mummy would stand up in the kitchen and cook’ and he said ‘no’. That was a bit of a sad moment, that he’s eight and he doesn’t have these memories that I would have liked them to have had.”

She still struggled to do things for herself and missed sport and the “rush” it gave her.

Then a turning point: She stumbled across news that Climbing NZ would be including a para-athlete category at the 2017 Nationals for the first time. 18 years after her accident, she started climbing again.

Competitive climbers usually lead-climb, taking the rope with them and attaching it to the wall with clips as they climb. That was too risky for Māia so she top-roped, having the rope come from above to give her a “safety net”. If she was to fall, she wouldn’t smash against the wall.

Māia discovered she could achieve more on the wall with “one and a half legs” than she ever had with two legs. She went to the 2017 Nationals – it was the first time she’d competed at that level, even before her accident.

Rachel Māia’s persevered with climbing even though her injured left leg slowed her down. Photo: Erana Pound @thecultureofgrace & @rachelmaianz

But there were issues. On the wall, she used her injured left leg to counter balance, but she couldn’t put weight on it because it was unstable. Her leg atrophied – the muscle had wasted away. Still, she persevered with her climbing as a way to manage life with a disability – on the wall she felt free.

She set New Zealand records and in 2018 became the first international New Zealand para-climber, finishing fourth at the IFSC World Paraclimbing Championships. Māia also set a New Zealand record as the first athlete to make it to the World Championship final.

It was at the World Champs that amputation first crossed her mind. She was climbing with friends, one of whom was a below-the-knee amputee. Māia realised she might be able to accomplish more with a prosthetic.

“It was while sitting on top of an Austrian mountain, in the serenity you find surrounded by foggy clouds far above the treeline, that I realised how big and how beautiful the world was, how much I wanted to throw myself into exploring it. And yet also how much my mobility was holding me back.”

When she returned home, she called her surgeon.

***

She sits in her hospital bed waiting for the doctors to tell her it’s time.

But at the exact moment they arrive Māia realises the black vivid pen drawn onto her left leg, to mark where it is to be amputated, has rubbed off onto her right leg.

She panics, seeing herself waking up missing the wrong leg. “You can’t take me,” she says through tears. The black marker is removed from her right leg and she re-focuses on the Titahi Bay waves.

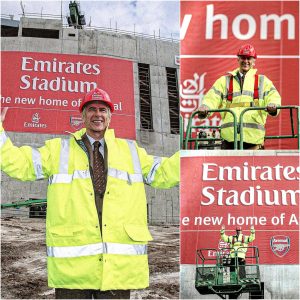

The boat sheds at Titahi Bay Photo: Carl Johnstone

Māia wakes with the sensation of water on her foot. Her plan to go to sleep thinking about those Titahi Bay waves on her feet worked so well that she’s still in the scene after surgery, but some pesky footwear has somehow inserted itself.

She calls out, “‘Excuse me, hello? Can someone take the jandal off my foot please? It’s really annoying!’”

A nurse comes over and quietly says, ‘Hey, you don’t have a foot anymore… you’re in recovery now’.”

***

48 hours later, in her hospital room, which looks out across the hospital car park and the lush green Otari Wilton Bush in Wellington, Tui and Kereru provide a dusk chorus punctuated by a beeping monitor.

Māia’s phone rests on her knees playing a video of the ocean lapping over her feet.

A nurse sits by her side, and slowly injects a nerve blocker into the top of her left leg. Maia stares at the phone and tries to focus on the water.

Her three children have been to visit, leaving gifts and a drawing on what remains of her left leg. A little red tongue pokes out of the bandages. “Meet Stumpy the Snake,” she laughs as she lifts her residual limb.

The children have put together a jar full of goals, scrawled on pieces of paper, they want their mummy to achieve. One son wants her to do the Tongariro Crossing with him. Another goal is to make a cookie mix with Mummy and then eat all the cookie dough instead.

Her most ambitious goal is to conquer the wall at this year’s Nationals in New Zealand and the World Championships in France in July.

“It’s going to be an interesting rehab because there’s going to be things that I feel like I should be able to do sooner than things that you would think you couldn’t do for a long time.”

Photo: Erana Pound @thecultureofgrace & @rachelmaianz

Māia knows she’ll be climbing before she can walk.

But she says she’ll feel like she’s collecting trophies long before she makes it to any competitions, if she can accomplish some of the little things – getting peanut butter out of the fridge for her children’s breakfast or holding their hands while they cross the road.

“They will be the small wins that are going to make my heart melt.”